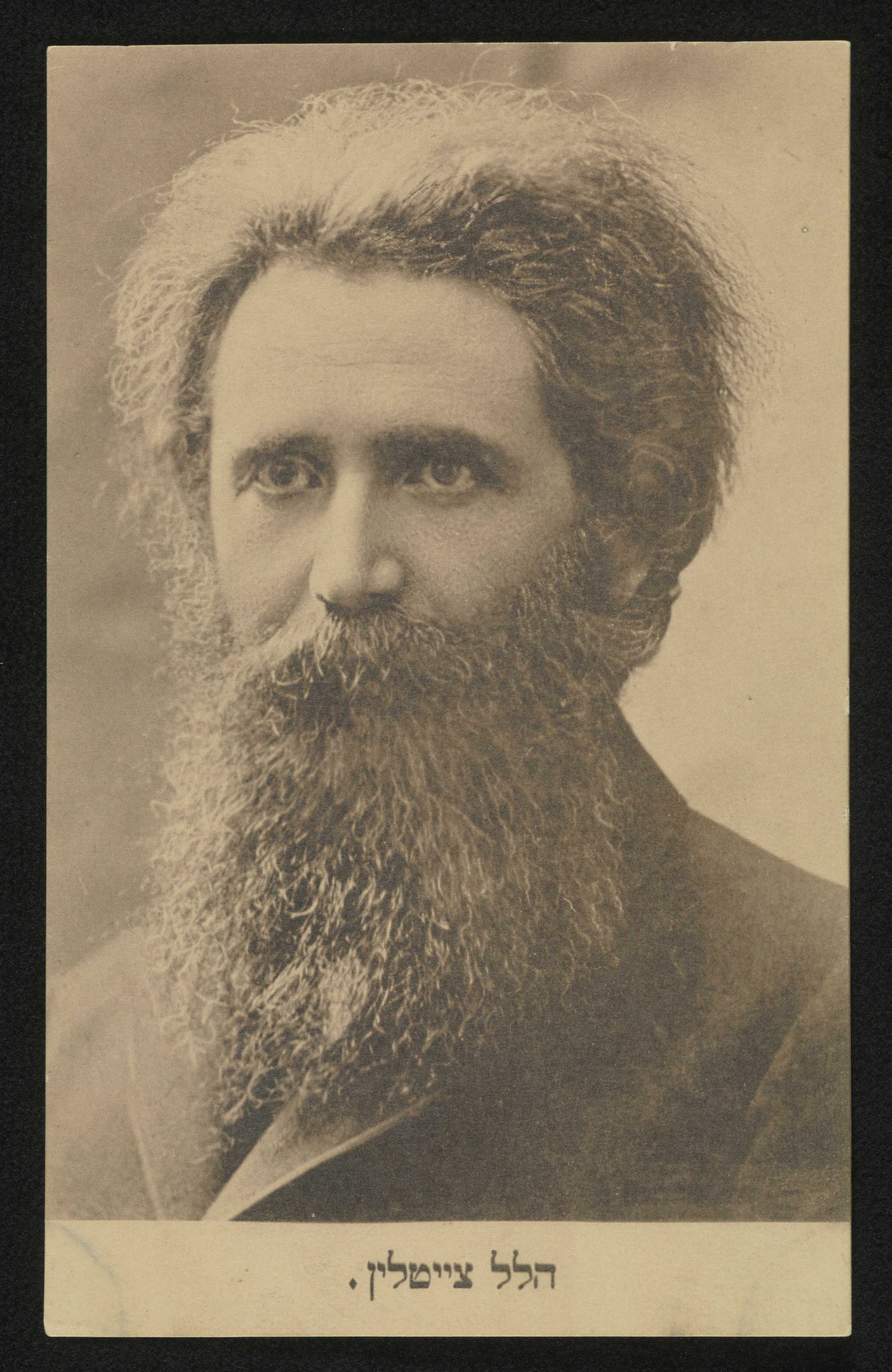

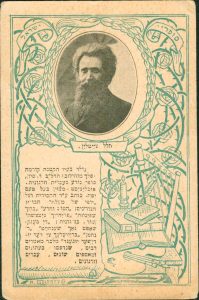

Though he saw the Jewish people as trapped in a fatal, dead-end existence, writer Hillel Zeitlin labored to bring redemption. Struggling with doubt, he kept hoping and praying, wrestling with contradictions to create a role model that – despite its lack of concrete success – resonates with Jewish intellectuals to this day

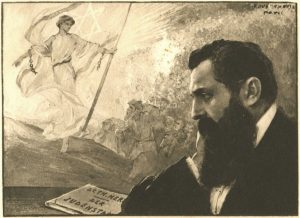

Wrapped in a prayer shawl, long hair flowing and brow crowned with tefillin, he walked to Warsaw’s deportation square, a volume of the Zohar tucked tightly under his arm. Upright and unswerving as a heavenly saint or a modern, monastical mystic going to meet his Maker, he was brutally cut down by the Nazis.

Such is the apocryphal description of kabbalist, journalist, and thinker Hillel Zeitlin’s death. He was the latest in a succession of Zionist martyrs such as Yosef Hayyim Brenner and Yosef Trumpeldor. His dramatic end shook the Jewish community in the distant land of Israel, awakening interest in and empathy for this enigmatic figure, even among his critics. No one knows if the aforementioned depiction is accurate or a new myth of Jewish self-sacrifice, adding Zeitlin’s religious fervor and resignation to a rich heritage of legendary rabbis and other righteous ones. Regardless, it’s a tale of an exalted death, the pinnacle of a life devoted to the very values it exemplified.

Three in Despair

Hillel Zeitlin was born in 1871 in Korma, a shtetl in the Mogilev governorate (today in Belarus). His parents belonged to the Kaposzt branch of Chabad Hasidim. An eager student, he possessed broad Jewish knowledge and an unquenchable thirst for religious depth and mysticism even in childhood. These set him early on the path of spiritual seeking, at first only within Jewish tradition but eventually encompassing the mystic heritage of many cultures and religions.

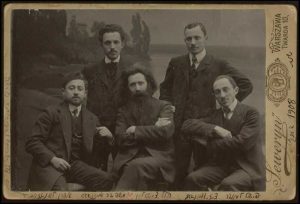

His father’s financial decline forced young Hillel to wander among the small Jewish towns of the Pale of Settlement, eking out a living as a teacher. Unmoored, Zeitlin roamed intellectually as well. Like many of his contemporaries, he was captivated by the great thinkers of his age, from Nietzsche’s compelling philosophy of doubt to Schopenhauer’s doctrine of blind will and fate and Lev Shestov’s grim subjectivism. Hillel married and moved to Gomel, where he found a group of like-minded and talented companions, all budding writers. Among them were Brenner (see “Nevertheless Zionism,” Segula 69) and Shalom Sander Baum. They were united by concern for the catastrophic state of the Jewish people, such that Zeitlin wrote, “Despair grew, and doubt, and with them [the call to] sacred poetry” (Hillel Zeitlin, Book of the Individuals: Collected Writings [Mossad Ha-rav Kook, 1979], p. 2 [Hebrew]).

Pessimism was popular in Europe at the turn of the 20th century, with many eastern European Jewish authors voicing such sentiments. Brenner and Zeitlin were among the most expressively urgent, describing the Jewish people as teetering on the edge of the abyss. In 1906, Brenner declared almost prophetically: “Six million are hanging by a scorched hair” (Yosef Hayyim Brenner, “He Sent Me a Long Letter” [London], p. 16 [Hebrew]).

The three young men felt isolated by their refusal to ignore this cruel reality. Fiercely individualist, they avoided the politics dividing Jewish society into parties and movements. For Zeitlin, Brenner, and Baum, both religion and ideology were just opiates of the masses, as likely to exacerbate the crisis enveloping Europe’s Jews as resolve it. Great schemes of emancipation or independence were mere delusions, and the politics driving them – Zionist or otherwise – were shallow and bourgeois.

Yet instead of being crushed by such a ruthless existence, the three were determined to act. Each went a different way, paying a different price. Sander Baum took his own life, having given up on finding a solution. Brenner put pragmatism before metaphysics, journeying to the land of Israel and devoting himself to the backbreaking task of building the land, vain as the hope of achieving anything substantial might be. His existential commitment to Jewish labor in the here and now took him far from religious tradition. Zeitlin chose yet a third path – mystic, Hasidic, messianic.

Facing the World’s Sorrow

In those years, Hillel Zeitlin was preoccupied with life’s inevitable pain and sorrow – both the internal, spiritual kind and the external, physical burden imposed by the pitiful conditions in which most Jews lived. His intellectual journey summoned Nietzsche, Spinoza, and Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav – whom he cast as a Jewish Faust – to his aid. Zeitlin’s writings chronicle his search for relief through many and varied means, and he composed many of his own prayers. He sought not just to ease his own melancholy, or even his fellow Jews’ suffering, but to heal a fractured world. In 1901 he averred:

When consciousness expands, man’s perspective on the essence of life expands accordingly, and he can understand all its sorrows. His empathy then extends to all of mankind, since in truth, all are suffering. […] He unites his life with theirs, becoming accustomed to placing their needs before his own. He begins loving his fellow man more and more. (Hillel Zeitlin, “Thoughts,” Ha-dor [The Generation] 10 [February 28, 1901/9 Adar 5661], p. 10)

Zeitlin attributed his Gomel circle’s resilience to its never-ending searching and its deep commitment to bettering the world. Both constituted a spiritual clarion call to fight to the bitter end:

By seeking and striving to correct the global evils of life and man, the iniquity of mankind’s eternal fall, some of us (i.e., Brenner, Sander Baum, and myself plus a few others) have arrived at the following thought: Life is full of tragedy and sin. Man would have been better off had he not been created. But since he has been, his task is to strive with all his might to improve and refine this life, imbuing it with heavenly sanctity. (Hillel Zeitlin, “Yosef Hayyim Brenner: Writings and Memoirs,” Ha-tekufa [The Times] 14–15 [Tevet–Sivan 5682], p. 635)

Did Zeitlin really live such lofty ideals? Yitzhak Sadeh, his student at the time of the Kishinev pogrom and later the first commander of the Hagana’s Palmah strike force, recorded the effect of these events on his teacher:

One summer evening is etched in my memory: a storm raged outside, and heavy rain pounded angrily on the roof and windows. Lightning flashed and thunder rolled. The roar of the storm woke me, and after the lightning I saw a scene I’ll never forget: Hillel Zeitlin was standing in the middle of the room in his white nightshirt, his face very pale, his eyes burning as he tore at the hair of his head, crying out in a choked voice, “Master of the Universe, Master of the Universe, see what You’ve done!” When he realized I was awake, he came over and sat by my side, stroking my hair for a long while in silence. Shivering with emotion, I understood that a great sorrow weighed on his heart. After a lengthy pause, in a faint, trembling voice, he began telling me about the riots and the disgraceful tragedy. He spoke very softly, and his eyes swam with tears. That night he mentioned [the need for] weapons, the concept of self-defense, and so on. Perhaps he never explicitly preached [violence], but the spirit of his words moved me to those conclusions. I decided I had to get hold of a revolver so as to defend myself and my family and friends, in order that such shame as had come upon the Jews of Kishinev would never befall me. (Yitzhak Sadeh, Writings, vol. 1, The Notebook Is Open: Various Autobiographical Notes [United Kibbutz Movement, 1980], pp. 189–90 [Hebrew])

At that time, Zeitlin still saw self-defense as an inevitable response to the pogroms. Although a Zionist, he favored any territorial antidote to his people’s suffering, however temporary. When the Uganda proposition was voted down, he renounced Zionism. His concern for Jewish survival, he commented, took precedence over a Zionist Utopia in the land of Israel.

The Believing Skeptic / Man in Search of God

In 1907, Zeitlin moved to Warsaw. His spiritual quest returned to religion, finding inspiration in the Hasidic and kabbalistic traditions with which he’d grown up. To his way of thinking, Nietzsche’s skepticism was rooted in man’s search for God:

The Torah states: “And God created man in His image, in the image of God did He create him, male and female He created them” (Genesis 1:27). Others came and inverted the verse: “And man created God in his image, in man’s image did he create Him.” […] And we, how shall we answer the latter? [Both] these and those are the words of the living God (Eruvin 13b). These twin depths meet at a single point; when we examine the very root of the matter, these two chasms become one.

“Come, let me show you where heaven and earth kiss” [paraphrasing Bava Batra 74a]. God created man; man created God. The latter part of the statement holds (ibid. 105a). But what kind of man creates? Refined man (associated with the highest kabbalistic world, that of Atzilut), created in God’s image. And when does he create? When [he feels] God’s kiss. (Hillel Zeitlin, “Shekhina,” in Zeitlin, Longings for Beauty: Three Essays, ed. Jonatan Meir and Lee Bartov [Blima Books, 2020], p. 68 [Hebrew])

If modern heresy deemed God an invention designed to meet a psychological need, Hillel Zeitlin asked the crucial question: what kind of man creates God if not one who thirsts for the Divine? This synthesis of religion and skepticism allowed Zeitlin to examine the former as both insider and outsider. Only the “believing skeptic” could say anything meaningful about the inward journey of the religious experience. Those hoping to truly evaluate religion had to be

]…] people in whom the flame had previously burned, and though now it had seemingly been extinguished, the embers still whispered beneath the ash heap. (Hillel Zeitlin, In the Secret Place of the Soul: Three Essays, ed. Jonatan Meir and Samuel Glauber-Zimra [Blima Books, 2020], p. 28 [Hebrew])

After years of searching, Zeitlin could verbalize the foundational truth of man’s yearning for the Divine, even if God hid His face or didn’t even exist:

Whether or not there’s water in the world, there most certainly is thirst! (Zeitlin, “The Thirst,” in Longings for Beauty, p. 110)

Zeitlin’s religious observance had its ups and downs, but seeking God was always paramount.

Visions of War

During World War I, Zeitlin began keeping a diary of celestial visions, mystic experiences, and messianic expectations. He sought a publisher, but everyone dismissed his modern prophecies. The diary was thus lost, although a few passages have survived.

Despite Zeitlin’s journalistic fame, many of his literary endeavors failed. His eccentric appearance, strange religious views, prophecies of rebuke, and attraction to mysticism were often derided.

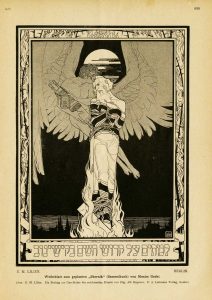

In 1921, historian and thinker Simon Rawidowicz suggested that Zeitlin produce a Hebrew translation of the Zohar with his own commentary. He jumped at this opportunity to reveal the great truths of Kabbala without any Zionistic leanings or academic obligations.

For Hillel Zeitlin, the Zohar resisted rational understanding; it had to be lived and breathed. Zeitlin supposedly labored over its translation for years, even after the Nazis invaded Poland and he found himself confined to the devastating Warsaw Ghetto. All we have of this magnum opus, however, is the introduction and a short, initial section. The rest may well lie buried beneath the ghetto.

In 1924, the ultra-Orthodox Agudath Israel party objected to Zeitlin’s highly personal, individualistic religious path and worked to delegitimize both him and his ideas, even resorting to bodily attacks. In response, the writer reiterated sentiments expressed in “The Thirst”: Faith isn’t a matter of sociological or political affiliation; it’s not what you do or who your friends are. It springs from the depths of the soul, from a clear and inexhaustible spiritual source:

If faith is no more than an external creed to which the heart must submit from within, a series of mechanical tasks to be performed with no great intent, meaning, or purpose, with neither love nor joy; if faith is only this and no more – as the window smashers, stone throwers, and book burners of Aguda define it – then I am interested only in “The Thirst” (as I expressed it sixteen years ago), […] whose essence is liberation – or, in Aguda’s eyes, “heresy.” But if faith is something more exalted – a godly life, the most internalized and innermost, the Holy of Holies of the soul, the chariot of the Holy King, a thirst for godliness, a longing for holiness, a constant fire that never wanes, an eternal quest, an everlasting drive to rise ever higher to perfection – then my “thirst,” though not a directly religious urge […], is a step toward that pure, deep faith […]. Yes, that is the way. Only this path leads to truth rather than fake [behavior] and cheap imitation. (Hillel Zeitlin, “My Heresy,” The Moment, 25 Sivan 5684/June 27, 1924, p. 4 [Yiddish])

This unusual outlook also underlay Zeitlin’s opposition to separate Jewish schools for each variety of observance and party affiliation.

The term “Torah” is frequently confused with the term “religion” as commonly used in Europe. But in truth the concept of Torah is far wider, deeper, and more varied than that of “religion.” […] I seek not dogmas but a living, [dynamic] Torah, a source of spiritual strength, a fount of creativity. (Hillel Zeitlin, “Timely Issues and World Issues,” The Moment, 29 Tishrei 5676/October 7, 1915, p. 3 [Yiddish])

Hasidism for the End of Days

During the 1920s, Zeitlin set up small messianic groups aiming to revive the Jewish people – particularly the younger generation – through Kabbala and Hasidism. These study and prayer circles bound members by strictures that Zeitlin believed would eventually produce a wider spiritual awakening. He hoped this movement would spawn a “latter-day Hasidism” essential to Israel’s redemption.

Despite the darkness and despair of his times, Zeitlin was profoundly influenced by Chabad Hasidism’s view of the world as infused with God’s presence. He saw faith, hope, and love as additional senses, sharper than the physical ones, allowing people attuned to them to perceive and meld the depths of reality, influencing its development. Such individuals could also intercede for those less spiritually aligned. In this vein, he addressed God:

Mankind has indeed moved far, far away from You. [People] cannot reach You. They’ve forgotten the way to You. They’ve forgotten Your Name. But when they seek joy, do they not seek You? And when they search for substance in their lives, do they not seek You? And when they look for life’s true meaning, do they not seek You? (Hillel Zeitlin, “Prayers,” Ha-tekufa 12 [5682], p. 376)

This prayer, entitled “If Not Now, When?” ended thus: “Reveal Yourself to all those on earth according to Your words: Behold, I am He who holds your lives, your happiness, and your truth in My hand. Come to Me!” (ibid.).

Zeitlin saw the Hasidic path of meditative worship and study as a means of refining and developing spiritual consciousness. He believed it could heighten dedicated, outstanding young Jews’ spirituality, thereby elevating the entire Jewish people. Recalling Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai’s aspirations to assemble a group of sages in Yavne to rejuvenate the people of Israel after the Temple’s destruction, Zeitlin called his circles Bnei Yavne, “Sons of Yavne.” They were to convey that redemption hung in the balance. He dubbed the more advanced cabals Bnei Heikhala, “Sons of the Palace,” referring to the palatial spiritual realms inhabited by Jewish mystics. The idea was to heal a shattered world. These pioneers, he hoped, would grow into a much larger movement, a Hasidism for the End of Days.

One small circle will reach out to the next, and that next to a third, until an entire assembly of the Children of Israel is formed, returning to God with truth and integrity. (Zeitlin, Book of the Individuals, p. 265)

Redemption from Within

This eschatological Hasidism was paradoxical, calling for a national revival that would somehow remain apolitical. Hillel Zeitlin’s revolution was to be utterly innocent, uncynical, and impartial.

Zeitlin envisioned a process of spiritual refinement that would correct all the flaws exposed by his journalistic coverage of the Jewish political movements, including the many branches of Polish Hasidism. His disciples would model a national identity without fascism or racism, a social equality without socialism, and an ideal society without political parties. But such perfection was way beyond the grasp – or the inclinations – of the Jewish masses:

The whole world cannot be repaired until first the dreadful sin committed by Israel throughout the past four thousand years is put right. Then [Israel] will organize its entire society – and the lives of its members – on the foundations of the Torah given to Israel at Sinai […]. And [the Torah] shall be the source of all truth and all love of truth, all grace and pardon, all innocence and uprightness, all the joy of life and all its sanctity. (ibid., p. 3)

Contrary to the methods he’d urged half a century earlier as a Zionist delegate, Zeitlin now relied on an elite acting independently within its own boundaries, because his direct attempts to reform Jewish society had failed. Disillusioned with both nationalism and Marxism – in fact, with “isms” in general – he’d come to believe that true social change could result only from personal refinement, and that only better individuals could produce a better world.

Zeitlin wandered between cities and shtetls, promoting his new approach by creating a study circle here and a meditative group there. His success was very limited, yet he refused to despair. Even in the Warsaw Ghetto, he clung to his belief in a redemption stemming from intensive self-work.

Before Rosh Hashana of 1941, Zeitlin invited over his friends in the ghetto:

I think we need at least the last Sabbath of 5701 to take stock and prepare ourselves to enter the “Sabbath” year [5702, numerically equivalent to the Hebrew word Shabbat). It will doubtless be a year of redemptive spiritual uplift. I am therefore inviting certain learned individuals to join me on the coming Sabbath. May it bring good tidings [conducive] to considering how we can appropriately usher in this Sabbath year in the manner known to the mystics. (Hillel Seidman, Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto, New York, 1957, pp 295-7, Hebrew)

Some claim Zeitlin could have escaped Poland but remained with his colleagues and friends in their hour of need, upholding his philosophy of looking sorrow squarely in the eye and attempting to redeem it through yearning, anticipation, and prayers for revelation and redemption. If there is pain in the world, he reasoned, man must seek God and demand that He reveal Himself.

Back to Zeitlin

Despite the yawning gap between the spiritual volatility of the turn of the 20th century and our present existential quest, scholars are reexamining Zeitlin’s views and work, partly due to the popularity of neo-Hasidism over the past three decades. Wherever this revival may lead, it clearly entails a return to kabbalistic and Hasidic sources and a determination to apply them in a modern context. In many respects, Zeitlin is the largely forgotten father of this movement, whose more recent leaders have included rabbis Abraham Joshua Heschel (who had been a young pupil of Zeitlin’s in Warsaw) and Adin Steinsaltz.

Zeitlin offers the Hasidically inclined a path that ignores neither political problems nor life’s challenges. His deep awareness of suffering led not to paralysis but to empathy, love, and yearning. Though known in his youth as “the heretic with tefillin,” he cut across sectors and identities, searching for God without necessarily believing in Him. According to Zeitlin, the terrible longing and existential thirst resulting from the hidden face of the Divine fuel constant spiritual advancement, inspiring both prayer to God and caring for others.