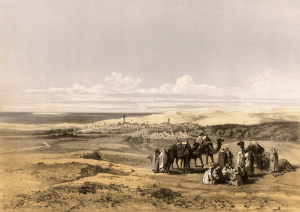

After touring the land of Israel, an early Zionist delegation proposed resettling European Jews not just in agricultural colonies but in cities. A pioneer group from Jaffa agreed to pave the way in Gaza, writing a new chapter in the turbulent story of Jewish settlement there

There’s been a Jewish community in Gaza ever since the late Middle Ages. In the 1600s, two of its distinguished members were the great liturgical poet Rabbi Yisrael Najara – who composed, inter alia, the Sabbath hymn Ya Ribon Olam and Yodukha Ra’ayonai – and Nathan of Gaza, who proclaimed Shabbetai Zvi the Messiah. At the turn of the 18th century, during the Napoleonic Wars, the Jews abandoned Gaza. As Rabbi Yehosef Schwartz (the first modern researcher of the land of Israel) wrote:

None of our nation is there now. Until 5559 [1799] there was indeed settlement there. But that year, French forces marched into the land with Napoleon Bonaparte, moving from Egypt to the land of Israel via Gaza, and it was a time of distress for the Jews of Gaza, and many fled. Since then, the group of our people [there] has dwindled, until in 5571 [1811] not one Jew remained, for they’d all gone to Hebron and Jerusalem. (Yehosef Schwartz, The Produce of the Land [Lvov, 1865], p. 65 [Hebrew])

Ibrahim Pasha subsequently destroyed the desolate local synagogue, using its stones to fortify Ashkelon during his 1831 revolt against Ottoman rule.

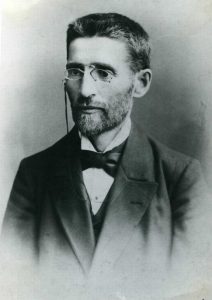

In 1881, after Jews were falsely implicated in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, a wave of pogroms broke out in Russia. In response, the Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) association in Ukraine sent member Zalman David Levontin (a Moscow bookkeeper) to the land of Israel in search of suitable areas for the resettlement of Jews seeking to leave Russia.

In 5642 (1882), Levontin formed the Yesud Ha-ma’ala Pioneer Committee in Jaffa, and he and Yosef Feinberg – his partner in founding Rishon Lezion, the first Zionist colony, that same year – set out to find land for a colony in the Judean Lowlands. With Jaffa and Jerusalem real estate prices inflated by European commercial interests, the pair headed south. In Gaza they encountered a Jewish convert to Christianity named Shapira – the only European in town – who arranged a meeting for them in Deir al-Balah with the local Bedouin chief. Levontin made three separate trips Gaza to finalize a land deal, but to no avail. Instead, at year’s end he acquired a site known as ‘Uyūn Qārā (Fountain of the Crier), on which Rishon Lezion was promptly founded.

Call of the City

On 12 Nisan 5645 (1885), Ze’ev Kalonymus Wissotzky (see “Just His Cup of Tea,” Segula 53), one of the heads of Hovevei Zion in Russia, was sent to check on the colonies the association had helped develop in the land of Israel. After touring the eight villages, and learning of their inhabitants’ distress, Wissotzky realized that such initiatives were no solution for the tens of thousands of Jews looking to settle in the land. The colonies were too small to absorb such masses, plus most Russian Jews were urban peddlers or professionals so they were neither interested nor skilled in agriculture. Wissotzky clarified his thoughts in a letter to Shaul Pinhas Rabinowitz, secretary of Hovevei Zion in Warsaw:

In my opinion, Hovevei Zion must open the eyes of our brethren who work as craftsmen and traders and tell them: Dear brothers, the Holy Land has many cities in which no Jews as yet live, such as Nablus, Nazareth, Ramle, Lod, Bethlehem, Gaza, Ashkelon, Tyre, Sidon, etc. Their inhabitants eat bread and wear clothes, and their feet are shod. They have many needs, and when Jews come there, they too will naturally find subsistence in time. Therefore, any carpenter, mason, or blacksmith among you who feels the pinch can assume that Gaza will be like Ponevezh, and Asdudd like Raseinē, and that just as he has found bread in Bialystok, Vilna, and Minsk, he’ll manage to live there [in the Holy Land]. (Haggai Hoberman, Jewish Community in Gaza [Reishit Yerushalayim, 2020], p. 41 [Hebrew])

During his visit, Wissotzky established Hovevei’s action committee in Jaffa and set to work implementing this plan. Merchant Abraham Muyal of Jaffa headed the committee, and his secretary was Eleazar Rokah. Wissotzky and Muyal recruited such activists as Aharon Chelouche, Hayyim Amzaleg, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, Yehiel Mikhel Pines, Zalman David Levontin, and Israel Dov Frumkin. Their discussions concluded that Gaza, Lod, and Nablus seemed promising, since job opportunities there were relatively plentiful. Despite his failed attempt to acquire land in Gaza two years earlier, Levontin believed in the city’s settlement potential and supported the initiative. Muyal, however, was the one charged with turning words into action.

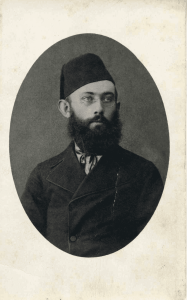

On Hol Ha-moed Sukkot 5646 (1885), Muyal met with young Jews from Jaffa originally from Africa’s Maghreb region. As Arabic-speaking Zionists who understood the local authorities’ mentality, the Jaffans were ideally suited to spearhead Jewish urban settlement among an Arab population. After Muyal explained the idea’s potential for the great wave of immigration expected from Russia, and their own crucial role as both pioneers and intermediaries between these arrivals and the Ottoman powers that be, his volunteers began eagerly preparing to move.

The first group of families settled in Lod, the second in Nablus, and the largest contingent – some twenty families – made their home in Gaza. Abraham Muyal died suddenly on 12 Tevet 5646 (1885) after a fall from his horse, but the settlers soldiered on without him.

Heading the Gaza group was Hakham Nissim Elkayam, son of Rabbi Moshe Elkayam, a leader of the Jaffa community. At first only the men moved to Gaza, but their families soon joined them. A description of the city by Rabbi Suleiman Menahem Mani, later rabbi of Hebron, indicates that by Kislev 5646 (December 1885) sixteen Jewish families were already in Gaza, and most were merchants. The Jews lived in spacious rentals in Al-Zeitoun, the olive oil production district in the south of the city and home to a relatively prosperous Christian population. To maintain social ties among themselves – and protect each other when necessary – they rented adjacent properties.

Adding to the Ranks

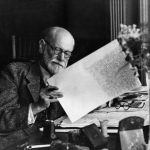

In Iyar 5642 (1882), Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, Nissim Bekhar, and Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Pines established the Rebirth of Israel Association, which championed the development of Hebrew as a spoken language, Hebrew nationalist education, and land purchases for Jewish settlement. Every two weeks, Ben-Yehuda traveled from Jerusalem to Jaffa to meet with young nationalists and reinforce the values of national revival. Some of these young men were among those who moved to Gaza, and Ben-Yehuda stayed in close contact with them.

When the Russian immigrants showed no interest in settling in Gaza, Ben-Yehuda encouraged others to do so – and to learn a trade rather than living off charity, as was unfortunately the norm among Ashkenazim in Jerusalem. Given the difficulties of making a living in the holy city with its glut of tradesmen, he offered two solutions: either study professions less common among Jews in Jerusalem, such as construction and masonry, or settle elsewhere in the land of Israel:

Regarding those who’ve already learned a trade for which there’s little demand in Jerusalem, such craftsmen should seek work somewhere other than Jerusalem. After all, thank God, the land is large and broad, with many towns lacking essential artisans. In Nablus, Gaza, Ein Ganim [Jenin], and the like, there’s no carpenter or ironworker, no tailor or cobbler. (“Ways of Acquiring a Profession in the Land of Israel,” Ha-zvi, 5 Av 5646/August 6, 1886, p. 1)

This call from the pages of Ben-Yehuda’s own paper made an impact, and a year later a group of Jerusalem professionals resolved to resettle in Gaza:

We the undersigned, all artisans living in great distress here in the holy city because of the abundance of craftsmen and lack of work […], have awakened to the sound of your words in Ha-zvi regarding our sorry state. We’ve seen that we really have no choice but to settle in one of the cities of the Holy Land in which there’s no Jewish community […], to settle ten families [representing] all kinds of craftsmen in the coastal town of Gaza, where the vision of craftsmanship hasn’t yet caught on, for there are no craftsmen among our Ashkenazic brethren there. Yet we won’t be able to achieve our goal without support and assistance in settling in this city until we can stand on our own two feet and live off the work of our hands. (letter to the editor, Ha-zvi, 6 Elul 5647/August 26, 1887, p. 3)

The Jerusalemites related that they had appealed to Jerusalem’s charitable Kollelim Committee, but that body had postponed discussion of their case with various excuses. And when it finally did discuss their appeal, the committee had supported the idea in principle but claimed insufficient resources to finance this settlement project.

Nonetheless, the initiative took shape, and Ashkenazic craftsmen and their families joined the Jaffa group already in Gaza:

What we said in Ha-zvi about settling the cities of the land has prompted a few craftsmen to settle in the town of Gaza. Rabbi Yisrael Hayat came here last week, having settled there some four months ago, and he told us that aside from a few Sephardic families living there, there are also twenty-three Ashkenazic ones, but they have no ritual slaughterer or schoolteacher. We advised him to appeal to the Kollelim Committee, in case it might help them. We hope the committee won’t refrain from supporting the new settlement. (“Jerusalem,” Ha-zvi, 12 Adar 5648/February 24, 1888, p. 5)

The Jaffa cohort remained in touch with Ben-Yehuda, and mutual visits to Jerusalem and Gaza were spent discussing how to develop the settlement. The Gaza community also used Ha-zvi to promote its affairs.

Bitter Fruit

The families from Jaffa had to find ways of earning a living in Gaza. Initially some worked in moneylending and exchange, as they’d done in Jaffa, but Gaza was too small to support many of them. Several turned to commerce, primarily among the Bedouin. All week, these Jews dragged their wares from one encampment to another , returning home only for the Sabbath. Jewish tailors, blacksmiths, and mattress manufacturers integrated into the local economy. Contacts were gradually made and trust built between Jews and their neighbors, and many Arabs preferred doing business with the newcomers, who were known for their honesty.

Before the Jewish settlement of Gaza, Jewish merchants had visited the town periodically. One such, Eliyahu Arvatz of Jerusalem, was asked by friends abroad to send them a fruit known in Arabic as handal (colocynth, or bitter apple), a watermelon-like gourd grew wild around Gaza and was used locally in medicines and occasionally to dye fabric but was generally considered worthless. As demand for handal grew, it was shipped to Germany, where it served as an ingredient in quinine, an anti-malaria medication. After the renewal of Jewish settlement in Gaza, Arvatz moved there with his family to oversee the business firsthand.

Eventually, other Jews (and Arabs) began exporting handal to Germany and barley to England for whisky and beer production. Hakham Yosef Ya’ir had trafficked in handal in Khan Yunis before relocating to Gaza with his friends from Jaffa. Moshe Arvatz, president of Gaza’s Jewish community, had come from Gibraltar to Jaffa with his family and – at Hakham Nissim Elkayam’s urging – settled in Gaza as well. A secret rivalry developed between these two wealthy men, and each opened a synagogue in his home.

As British subjects, the Jewish merchants from Gibraltar received a license to export to Europe, giving them an edge over their Arab competitors, who had to use Jewish merchants from Libya as middlemen.

Due to Gaza’s gently sloping beaches, large freighters anchored far from the shore, complicating commerce. Porters trudged through the water, lugging sacks of merchandise on their backs to small boats waiting dozens of meters offshore, which then ferried the goods to the ships. After stumbling porters kept dropping their burdens into the sea, Gaza’s Jewish entrepreneurs hired a Jewish firm from Jaffa to build the town’s first quay, making waves as the land of Israel’s first Jewish-manufactured port.

Southern Comfort

Further efforts to bring Jews to Gaza were fruitless, and the community grew only slightly. In the early 20th century, the city numbered roughly ninety Jewish families. The immigrants who arrived en masse from Russia didn’t settle in Gaza due to its hot climate and poor sanitation and because these newcomers didn’t speak Arabic. Jaffa resident Menahem Sheinkin, cofounder of the Ahuzat Bayit Association (which founded Tel Aviv in 1909), wrote of his visit to Gaza:

There are now […] only some thirty-five Jewish families, including three Ashkenazim […]. The Gaza Jewish community could have increased substantially, the main condition being the acquisition of land for a Jewish suburb, ideally on the way to the beach. (Zvi Shiloni, “Ahuzat Bayit in the Gaza Dunes? Plans for a Jewish National Suburb,” Studies in the Revival of Israel 25 [2015], p. 400 [Hebrew])

The idea of a Jewish suburb may have been prompted by Ottoman intentions to erect a modern residential area between Gaza and the coast. Two years later, in 1908, a neighborhood was planned northwest of Gaza, to be named A-rimal – “The Dunes” in Arabic. Inspired by this government activity, the Jews began working toward a Jewish area in the new district, hoping to attract wealthy, well-educated Jewish professionals. Yet the Young Turk Revolution that year and other disruptions within the Ottoman Empire prevented the scheme from moving forward.

Meanwhile, the Land of Israel Bureau was established in Jaffa as the Zionist Organization’s executive arm of the in the land of Israel. Headed by Arthur Ruppin, the bureau promoted settlement, so the Gaza settlers hoped the office would champion their efforts. In the summer of 1909, community president Moshe Arvatz, Mukhtar Hakham Nissim Elkayam, and Hakham David Amos met with Ruppin in Jaffa. Also present were Ahuzat Bayit cofounder Yehezkel Denin and Anglo-Palestine Bank director Zalman David Levontin, who’d backed Gaza settlement since its inception.

The settlers told those in attendance that Hovevei Zion’s Action Committee had disappointed them by failing to bring eastern European immigrants to Gaza. The pioneers asked the Land of Israel Bureau to implement the plan for which they’d given up the good life in Jaffa and settled in Gaza. During the meeting, community leaders proposed the purchase of cheap Arab land near Gaza and pushed for the establishment of a beachfront neighborhood similar to Ahuzat Bayit, which had recently been built north of Jaffa. Ruppin and his deputy, Dr. Yaakov Tahon, promised to look into it. However, they soon announced that they couldn’t help.

Undaunted, the Gaza residents arranged another meeting with Ruppin that autumn. This time he granted their request, evidently because negotiations had progressed regarding the purchase of the lands of Ruhama (see below) – not far from Gaza – and because the new Arab leadership in Gaza supported cooperation with Jews.

Within weeks, Ruppin headed a delegation to Gaza. The visit made a powerful impression on the delegates, and Ruppin sent a detailed, confidential memo to Zionist Organization president David Wolfson and the Zionist administration, in which he proposed that Jewish settlement in Gaza be expanded by means of a small Jewish residential area separate from the town. His rationale:

Jewish women find it hard to live among the Arabs in Gaza, who won’t allow an unveiled woman out on the street. (ibid., p. 403)

By June 1910, the government had already surveyed all the dunes between the city and the shore, dividing them into small, reasonably priced plots for imminent sale.

Things finally seemed to be going somewhere, and a Jewish school even opened in Gaza on 14 Iyar 5670 (1910). It taught Bible and Talmud in Hebrew, as in existing institutions in Jerusalem and Jaffa. Some opposed this everyday use of Hebrew on religious grounds, fearing a gradual desecration of the holy tongue. They also objected to the school’s inclusion of secular subjects, regarding even Bible study as a departure from the traditional yeshiva curriculum. Yet the proponents won out. and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda dispatched educator Eliezer Zeldes to serve as teacher.

Thanks to support from the Hovevei Zion committee in Odessa, a school has opened in Gaza. The Jewish community in Gaza remains small, and a school with one teacher will meet its current needs. The instructor is [community] member Zeldes, who originally taught in one of the modern heders in Russia and then studied in university in Switzerland. (Ha-olam, 23 Sivan 5670/June 30, 1910, p. 14)

Shattered Dream

With the purchase of land for a Jewish cemetery, the election of a community council, and the opening of the first Jewish school, there were high hopes that the small colony, still only numbering about thirty families, would thrive and expand. This optimism was fueled by the establishment of the neighboring Ruhama farm in 1911, ongoing plans for the A-rimal neighborhood, and the opening of a branch of the Anglo-Palestine Bank in Gaza in the spring of 1914. Concurrently, however, a four-year drought devastated the region, prompting the departure of most of the settlers. By 1913, just sixteen Jewish families remained.

The A-rimal neighborhood was put on hold as well, and in the summer of 1911 Zeldes lamented:

The three months designated by the local leadership for the sale of beachfront property have already passed, but the sale has yet to begin. (The Young Worker, 4 Elul 5671/August 28, 1911, p. 15 [Hebrew])

The delay apparently stemmed from the precarious financial state of the Ottoman Empire coupled with local bureaucracy. In any case, thus ended the dream of a Jewish neighborhood along the Gaza shore.

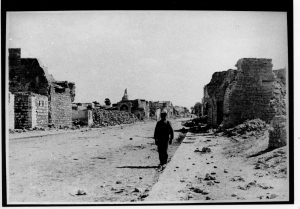

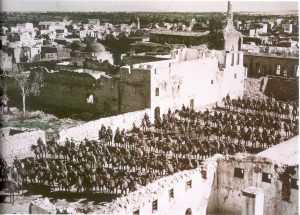

With the outbreak of World War I, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers and expelled all subjects of its allied foes, Russia, England, and France – including most of the Gaza Jewish community. In the spring of 1917, Gaza was evacuated, becoming a battleground for the British and Ottoman armies.

Once the war in the south had died down after the British conquest, Nissim Elkayam visited Gaza. He found the city in ruins and desperate for craftsmen to rebuild it. With his warehouse of merchandise intact and his Arab neighbors eager for his return – as Arab nationalism was still in its infancy – Elkayam decided to resettle in Gaza with son Shlomo, who worked in renovation. Nissim’s wife Mazal refused to accompany him, however, remaining with their young family in Jaffa’s Neve Zedek district. Elkayam urged those who’d left Gaza to follow his lead, but their Egyptian exile as enemy aliens during the war had left them too sickly and weak for new adventures.

The first Jewish family to heed Elkayam’s call was that of Eliezer and Tzila Margolin. The couple purchased the local flour mill from its German owners, who were classified as enemy subjects under British military rule. The Margolin home was soon hosting every Jew visiting the city, and a new nucleus of tradesmen gradually formed around them, willing to try their luck in Gaza. Even the local Arabs admired the Margolins, relating to Eliezer as the head of the Jewish community, appointing him to the municipal magistrates’ court, and involving him in city council meetings.

During the Arab riots of 1921, all the Jews apart from the Margolin family fled. Returning a few weeks later, they found their property virtually untouched. The following winter, the Shimshon elementary school opened in Gaza. Yet the community of fifty never grew, and the school closed two years later.

The Arab Revolt of 1929 put an end to most of the Jewish communities in Arab towns. On 19 Av that year, all forty-four Jewish residents of Gaza left, never to return.