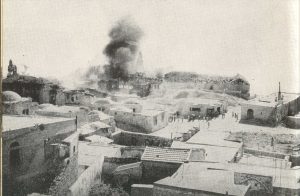

As the sun set on the British Mandate and rose over the new State of Israel, civil war raged between Arabs and Jews. Jerusalem’s hundred thousand Jewish residents prepared to celebrate Pesach under siege, unsure whether they were headed for redemption or for exodus from another kind of Egypt

In November 1947, the United Nations approved the partition of Mandate Palestine, designating Jerusalem as an internationally governed enclave intended to serve as a bridge of peace between the proposed Arab and Jewish states. Immediately after the UN vote, fighting broke out between the city’s two populations, disrupting normal life and causing no few casualties. One long, narrow route, winding mostly through hostile Arab villages, connected Jewish Jerusalem with the rest of the country’s Jews. The enemy took full advantage of this weakness, essentially placing the city under siege. Supply convoys were frequently attacked, usually near Sha’ar Ha-gai, where the road was hemmed in by hills.

Essentials soon dwindled, and the situation grew dire. Outlying Jewish settlements reliant on Jerusalem, such as Neve Yaakov and Kibbutz Ramat Rahel, suffered similarly. Some one hundred thousand Jews – a sixth of the Jewish population – were imperiled by the conflict. And when spring rolled around, all of them – from the ultra-Orthodox Neturei Karta sect to the largely irreligious members of Ramat Rahel – were busy preparing for Pesach.

The weeks leading up to the holiday were darkened by loss. Eleven members of a convoy to Har-Tuv (see “Doctor under Fire,” Segula 66) were killed after a dangerous mission on March 17 (6 Adar II); fourteen more were murdered on the Fast of Esther (March 24 that year) while transporting goods to Atarot, an agricultural village slightly north of Jerusalem. And two days after Purim, on March 27 and 28, another fifteen lost their lives in the Nebi Daniel convoy, having delivered critical supplies to the besieged Etzion Bloc. The Jewish-owned armored vehicles and trucks were captured by the Arabs, leaving Jerusalem’s military command without much of a fleet.

The next few days brought further casualties in the struggle to equip other parts of the country. The Yehiam convoy lost forty-six men, and another twenty-four were slain outside Kibbutz Hulda.

Pesach was a special challenge, as the holiday’s seven-day ban on bread required all manner of irregular substitutes, which the convoys clearly couldn’t deliver.

So the pre-state Jewish community’s leadership devised a new strategy. Instead of attempting to secure exposed vehicles, they’d take control of the road itself. Operation Nahshon was launched on April 4, on the night of 26 Adar II. Fifteen hundred fighters armed with newly arrived weapons (smuggled in over land and sea despite the British embargo) managed to hold the route long enough for nine hundred tons of supplies to reach Jerusalem in two convoys. Two hundred twenty-five trucks, mostly volunteered by their owners, took part.

No Matza

On 25 Adar, just before this immense effort began, Jerusalem regional commander David Shaltiel’s military adviser, Fritz Eshet, flew from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv to report to David Ben-Gurion. With no bread even in his own home, Eshet warned that matters could easily deteriorate:

The population is hysterical […]; there are no stocks of food; […] the Romema neighborhood has had no water for the last thirty-six hours […]; the [civilian] rear is expected to cave. (David Ben-Gurion, 1948–49 War Diary [Ministry of Defense, 1982], vol. I, p. 340 [Hebrew])

The next day, David Ben-Gurion announced to the Zionist Workers’ Party committee that Jerusalem was the land of Israel’s soul and that its needs therefore took precedence over everything else.

It’s [too] easy to starve it, parch it, and silence it […]. As long as there’s a choice between Jerusalem and elsewhere, Jerusalem comes first. (David Ben-Gurion, In Battle [Israel Workers’ Party, 1950], vol. 5, p. 298 [Hebrew])

Dov Yosef chaired the Jerusalem Emergency Committee, which oversaw the city’s supply line. He described the severe food shortages in early March:

We lacked animal proteins, and apart from flour we had [staples] for only four to fifteen days. (Dov Yosef, The Faithful City: The Siege of Jerusalem, 1948 [Simon & Schuster, 1960], p. 84)

Jerusalem’s Sephardic chief rabbi, Ben Zion Meir Hai Uzziel, had been stuck in the city for six months, separated from his children. He wrote to them a week before Pesach:

No one knows yet what will happen on Pesach, but in any case everything will be rationed and in short supply […]. Under these circumstances, there’s no hope of our all sitting down together as a family for Seder night, and I can’t imagine how miserably lonely that night will be. (Rabbi Ben Zion Meir Hai Uzziel, Treasures of Uzziel [ Rabbi Ovadya Yosef Publications Committee, 5767], vol. 5, pp. 558–59 [Hebrew])

Rabbi Dr. Tuvia Guttman, who lived next to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Me’a She’arim, wrote similarly in his memoirs:

The days before Pesach are especially difficult for us. No food is available on the regular market, apart from rations, which have rightly been minimized […]. On the black market, if you have connections, you can get a few small items at full price, like a tin of sardines, a jar of jelly […]. As yet we have no matza, and we’re very concerned. (Rabbi Dr. Tuvia Guttman, Jerusalem’s War of Liberation in 1948, p. 40 [Hebrew])

Operation Harel began on April 15 (6 Nisan), bringing two large convoys of 442 trucks carrying 1,800 tons of supplies. Palmah forces who’d been guarding the route to Jerusalem were moved into the city in preparation for Operation Jebusite – aimed at securing strategic sites abandoned by the British – so the road was once again blockaded.

The provisions delivered via operations Harel and the Nahshon vastly improved conditions in Jerusalem as Pesach approached. The convoys were welcomed by a joyous crowd, and the Jewish population rallied. Even isolated spots such as the Old City’s Jewish Quarter, Mount Scopus, and Neve Yaakov were resupplied, including Pesach food.

Desperate Measures

Due to the national state of emergency, the Chief Rabbinate issued special Pesach instructions:

Unground rice and the following legumes are permitted [for Ashkenazic Jews, who usually avoid them on Pesach]: peas, green beans, lentils, beans – as long as they’re set aside three days before the holiday and checked very carefully for stray grains. Likewise, this Pesach, pickled fish (lakerda) is allowed after it’s been thoroughly rinsed. Powdered milk, powdered eggs, and dried potatoes imported from the U.S. by the government Acquisitions Department are kosher for Passover. (“Permission to Eat Rice and Legumes on Pesach,” Ha-tzofe daily, 10 Nisan 5708/April 19, 1948, p. 3)

Similar messages regarding a variety of food products – including hake, lakerda (a Turkish dish made of cured bonito or mackerel), herring and sole fillets – were sent out by the ultra-Orthodox rabbinate and Jerusalem’s Council of the Ashkenazic Community.

The chief rabbinate of Petah Tikva claimed that flour flown in from Australia might be leaven, as it was made from rinsed grain. Pre-state chief rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog consulted Prof. Avraham Reifenberg, who lectured on agriculture and chemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His answer was definitive:

Grain can become leaven only when it has swelled. The fermentation process begins only at the time of swelling. The amount of water added prior to grinding, and its continued effect, is much less than required to allow any such expansion, so the question must be answered in the negative. The grain and flour are kosher for Pesach. (State Archives, Rabbi Herzog Archive, P-39/4243 [Hebrew])

Bitter herbs were another problem. Arabs from nearby villages such as Silwan and Lifta usually provided the requisite lettuce, but Arab produce deliveries had been suspended due to the ongoing hostilities. One solution was a local vegetable garden grown by Yehoshua Avizohar, a chemistry and biology teacher. Avizohar handed out lettuce to anyone who asked.

Another source was the fields of Deir Yassin, an Arab village captured by the Irgun militia earlier that month. The dean of Porat Yosef Yeshiva, Rabbi Ezra Attiya, asked Jerusalem’s Ashkenazic chief rabbi, Zvi Pesach Frank, if lettuce from the village was considered stolen and therefore forbidden. Rabbi Frank responded at length, concluding:

The land was acquired by the Hagana defense forces by conquest in war, and those Israelis gathering bitter herbs there evidently do so with the Hagana’s ]tacit[ permission. (Rabbi Zvi Pesach Frank, Har Zvi Responsa, Orah Hayyim 2:74 [Hebrew])

Seder in Ramat Rahel

Although Kibbutz Ramat Rahel is just south of the Jerusalem neighborhoods of Talpiot and Arnona, the cooperative was cut off during the war and reachable only by armored convoy. Kibbutzniks stranded in Jerusalem were given room and board in a wing of the Tnuva dairy factory on Yehezkel Street, in the heart of the city. The kibbutz tried to carry on as usual, and all members were requested to return to Ramat Rahel for its communal Seder.

This was no simple matter. On 13 Nisan (April 22), two days before Pesach, kibbutzniks Malka Hotnitzka and Yitzhak Zikhler were killed in an Arab attack on Ramat Rahel. The funeral was held that afternoon with minimal attendance. Both were buried temporarily in the kibbutz orchards, as the cemetery was too exposed to fire from enemy outposts. Obviously, the tragedy put a damper on Seder preparations. Yisrael Kauffman wrote later in a kibbutz publication:

Nevertheless, we decided to hold the Seder. We all sat down together in the large dining hall in semi-darkness – children and adults. The children sat in a semicircle; there was no singing or dancing. We read the Haggada. A stifled pain pierced every heart; there wasn’t a dry eye. After an hour we dispersed, hurrying to the guard posts. (Yisrael Kauffman, “Members’ Stories,” in Ramat Rahel in Battle [Kibbutz Ramat Rahel], p. 43 [Hebrew])

A passage paying tribute to Zikhler also mentioned that Seder night:

The next evening we sat down together at the Seder. We told the story of the exodus from Egypt, eulogized our fallen, and told our children – including the four orphans among them – Yitzhak Zikhker’s last wish, expressed not in words but in action: to fight to the end. (ibid., p. 100)

Ten more from Ramat Rahel were killed in battle, and the rest were evacuated to Jerusalem.

After the war, the entire kibbutz was practically destroyed and required rebuilding. Despite all the difficulties, including a heavy snowfall in 1949, the collective was determined to continue its Seder tradition. Seated in the dining hall, its walls riddled with bullet holes and its roof leaking after the intense shelling, members were joined by soldiers still stationed there in defense of the kibbutz. Together, they did whatever they could to make it a joyous Seder: the women used the few products available to cook up the best dishes they could, and the tables were laden with a surprisingly varied, tastefully served feast. All agreed that, circumstances notwithstanding, Ramat Rahel had acquitted itself admirably even in its darkest hours.

Night of Watching

In some places, guard duty and clashes with the enemy prevented everyone from sitting together at the Seder. Defenders of the Old City, for example, split into two groups, taking turns keeping watch. Yitzhak Avigdor Orenstein, rabbi of the Western Wall, presided over the first Seder, while the second was hosted by Reuven Spanier.

Even after Pesach, Old City residents went on eating matza, as there was nothing else. Fighting intensified until the Jewish Quarter surrendered to the Jordanian Arab Legion, and all combat-age men were taken into captivity in Jordan. The women, children, and elderly were transferred to the newer Jewish neighborhoods outside the Old City walls. Many of these refugees took their remaining matza with them, assuming food was scarce in the rest of Jerusalem as well.

The night before the Seder, those defending the nearby Jewish farming village of Neve Yaakov (now one of Jerusalem’s northern suburbs) were summoned to the main highway at midnight to unload supplies. The staff of a British armored car had been bribed to deliver the goods. Within ten minutes, the men had offloaded thirty packages of matza, wine, ammunition, and letters, and the vehicle was on its way back to Jerusalem without the enemy noticing a thing.

In Neve Yaakov, Seders were held in three homes, with the menfolk taking turns guarding. The menu: matza ball soup and kosher-for-Passover canned goulash someone happened to have. When shots rang out, everyone rushed to his post. All was soon quiet once again, and each Seder continued.

Zvi Tal, later a Supreme Court judge, was living in Neve Yaakov and serving as a communications officer. He wrote in his diary:

Lots of work to do making the kitchen kosher [for Pesach]. We have wine for the four cups [drunk at the Seder], but in the [Jordanian Arab] Legion’s last attack some bottles of DDT shattered and spilled on all the matza. We’re eating rice and legumes and hubbeza [mallow] stems. Certain passages in the Haggada brought tears to the eyes. (Zvi Tal, Diary of the Siege and Battles in Neve Yaakov, Ammunition Hill Archive [Hebrew])

The mukhtar of the Beit Yisrael district, Rabbi Moshe Yekutiel Alpert, missed his own Seder. Two Hagana fighters and a passerby were killed in his neighborhood the day before Pesach, and he was asked to help bury them. Alpert got home close to midnight, when the Seder was already over.

Seder in Schneller

That same Pesach eve, company commander Yaakov Salman alerted his men that they’d be evacuating women, children, and the elderly from Neve Yaakov and Atarot. The troops would be crossing enemy territory, and everyone was tense. One soldier subsequently recalled that an odd thing happened as they were preparing for the mission:

Suddenly an elderly man entered the room, his snow-white beard lending his face a strange majesty. He greeted us, took out a prayer shawl, spread it over his head, and recited a few blessings, and we all answered, “Amen.” He took some small pieces of parchment from his bag and gave one to each of us. I folded mine over and put it in my shirt pocket. When he’d finished, the mysterious guest left the room. (Meir Avizohar, Moria in 1948 Jerusalem: The First Hish Brigade in the Battles for Jerusalem [Lod, 2002], p. 99 [Hebrew])

Just then, Salman came and announced that the operation had been cancelled. He invited all the soldiers to a Seder in the mess hall of the Schneller army camp, which had been a German Protestant orphanage and school until the war began. The fighters were convinced that the old man had been none other than Elijah the prophet and would reappear when the cup of wine was poured in his honor during the Seder – but they were disappointed.

Instead, another white-haired gentleman turned up at the festivities, admittedly a little late. David Ben-Gurion had arrived in Jerusalem with the second large supply convoy on 11 Nisan (April 20) and remained to help boost the defenders’ morale and collaborate on decision making.

The day before Pesach had been particularly difficult for him. He’d been informed of yet another failure to capture the strategic hill of Nebi Samuel, just north of the city, with heavy casualties. Armored cars and vital weapons and ammunition – including a Davidka mortar (see “In a Word,” p. XX) – had fallen into enemy hands. And And Operation Jebusite’s commanders clashed about how to loosen the stranglehold gripping Jerusalem and its environs.

Having made sure there were adequate forces on hand to seize British military positions the moment they were evacuated, and having prepared for any Arab attempt to avenge the loss of Haifa by capturing Jerusalem, Ben-Gurion found time to join the soldiers’ Seder.

Run by Rabbi Yaakov Berman, this Seder was attended not only by Jerusalem commander Shaltiel but also by Chief Rabbi Herzog and his son Hayyim, who was liaising between the Hagana, the British Mandate authorities, and the supposedly impartial United Nations delegation overseeing the British withdrawal. Hayyim Herzog had invited Norwegian colonel Rosser Lund, the pro-Jewish UN military attaché, acting as his interpreter. Hayyim later recounted that the meal was sparse and far from festive, but the Seder was one of the most impressive he could remember.

Ben-Gurion greeted those present:

Let it be known to Jewish Jerusalem: The brunt of the war and its blows have fallen upon you, for you are the focal point of the battle. Let your spirit not be downfallen. You’ve bravely withstood all the terrible suffering. The entire Jewish people – and the flower of our youth – stands with you. The defenders and drivers [of the convoys] have risked their lives for you and will continue to do so. The ring of enemy outposts to your west and to the north is gradually being destroyed and conquered by our fighters. (David Ben-Gurion, When Israel Fought [Tel Aviv, 1951], p. 98 [Hebrew])

The future prime minister concluded by paraphrasing Psalm 137: “We will not forget you, O Jerusalem – our right hand shall not be forgotten” (ibid.).

Many soldiers had to leave the Seder to go on duty, while others joined midway through. Ben-Gurion’s speech was intended to encourage these men, but their bravery likely encouraged him as well after that draining day.

To Each His Own

The story of Israel’s passage from slavery to freedom resounded with special significance that Seder night in 1948. The yoke of the British Mandate would soon be replaced with Israeli independence. The tension of that “night of watching” (Exodus 12:42), as once experienced in Egypt, was palpable not only at every Seder in Jerusalem but in its streets. Yet each sector of the Jewish population felt the strain differently.

The anti-Zionist Neturei Karta community published its own mocking set of “Four Questions” for the Seder, attributed to the pseudonymous “He Who Knows How to Ask” (as opposed to the fourth son in the Haggada, who “doesn’t know how to ask”).

Our forefathers […] never even considered the idea of forcibly pursuing sovereignty and political independence […], but tonight many of the great and worthy have been captivated by this worthless ideal of forcefully throwing off the yoke of our exile. (He Who Knows How to Ask, “Why Is [This Night] Different?”Ha-homa [The Wall], 13 Nisan 5708/April 22, 1948, p. 2)

Nathan Feinberg and his wife, who lived in the relatively prosperous Rehavia neighborhood, joined friends for the Seder. The Feinbergs made their way gingerly through the streets for fear of shelling, and the gift they brought their hosts was half a bottle of kerosene, which was hard to come by and extremely useful in those days of scant electricity.

Hadassa Avigdori-Avinadav was among the volunteers who’d accompanied the convoys, though she lived in Jerusalem. She shared the Seder with the hundreds of drivers and their guides, all stuck in the city until its access road reopened.

After a long period of scarcity, the houses suddenly felt full of plenty […]. Throughout Pesach, there were battles in and around Jerusalem. Our young men were called up in the middle of the Seder and haven’t been home since, but apparently there’s no call for us women. (Hadassa Avigdori-Avinadav, The Way We Went: From a Convoy Guide’s Diary [Ministry of Defense, 1988], p. 105 [Hebrew])

Zipporah Porath, a young American studying at the Hebrew University that year, joined the Hagana and trained as a medic. Writing to her parents, she described her impressions on the way to and during a friend’s Seder that night:

It was a wonderful evening, a huge moon floating in a bathtub of blue […]. Not a shot to be heard the whole way. We were in high spirits, stopped off to bid Chag sameach (Happy holiday) to mutual friends, sang loudly and waved to people sitting on their balconies enjoying the quiet and waiting for Seder guests. Everybody has guests this year. There are about a hundred drivers in town who brought the last convoy to Jerusalem, stranded away from their families, and of course hundreds of soldiers far from home. […]

The herbs were truly bitter, plucked from the fields, like the greens we now eat with our daily fare. The charoset tasted every bit like the Egyptian bricks it was supposed to represent, although in these times there’s no way of knowing what it was made of. […] Despite the terrible food shortage, a meal of sorts was served, simple but plentiful, with kneidlach [matza balls] made from something that tasted like nuts. When the singing started it was really joyful. (Zipporah Porath, Letters from Jerusalem 1947–1948 [Jonathan Publications, 2008], pp. 149–52)

Walking home, Zipporah passed a Haredi neighborhood:

At one house we saw by the flickering candlelight in the window a large family group huddled around the holiday table, the youngsters’ earlocks dangling […], all singing with Hasidic fervor, transported with joy. Their singing had a haunting quality I cannot convey. Every corner of the deserted cobblestone alley reverberated with the sound of it, echoed and reechoed from every house. We hit the open road near Romema and broke into song ourselves, joined by the guards we passed at the various checkposts and roadblocks en route. (ibid., p. 152)

Indeed, for everyone in besieged Jerusalem that Pesach, the Seder of 1948 was unforgettable.